Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art New York George a Hearn 1906

If information technology were somehow possible to strip them of their content, the paintings of Winslow Homer would yet exist immensely satisfying. His oils and watercolors establish the best pure painting in nineteenth-century American art. In that location's a tremendous, and oftentimes abrasively sensual pleasance to Homer's surfaces. Call it tactile friction, which manifests in the oil paintings as a multitude of varied surfaces, and in the watercolors through the counterpoint of transparent and opaque paint. Friction also exists in Homer's designs, in abrupt changes of value and a fondness for irregular shapes.

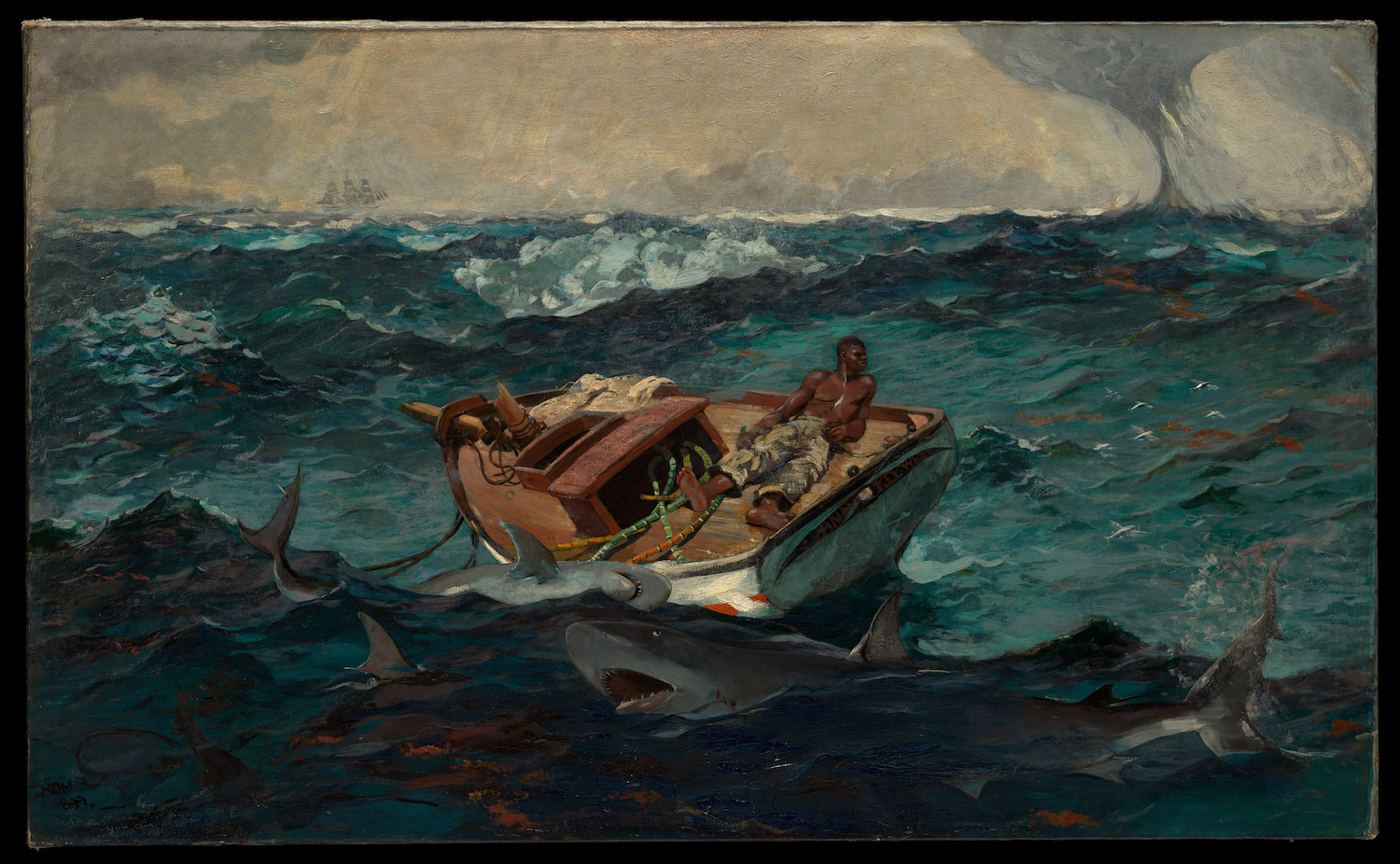

Of form, information technology'south neither possible nor necessary to view Homer in formal terms lonely. His work contains plenty of thematic friction, which the artist was loath to explain. This is the subject of Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents, a fairly perfect exhibition curated by Stephanie L. Herdrich and Sylvia Yount, recently opened at the Met. We know he wanted the work to speak for itself, and except for the titles, Homer offered niggling or no caption of his intent. The well-nigh famous example of Homer'south reticence—indeed, irritation— when pressed on narrative was his response to questions about The Gulf Stream.

I regret very much that I have painted a picture show that requires any description….I have crossed the Gulf Stream ten times & I should know something about information technology. The gunkhole & sharks are outside matters of very little consequence. They have been blown out to sea past a hurricane. Yous can tell these ladies that the unfortunate negro who now is so dazed & parboiled, will exist rescued & returned to his friends and domicile, & e'er later live happily.

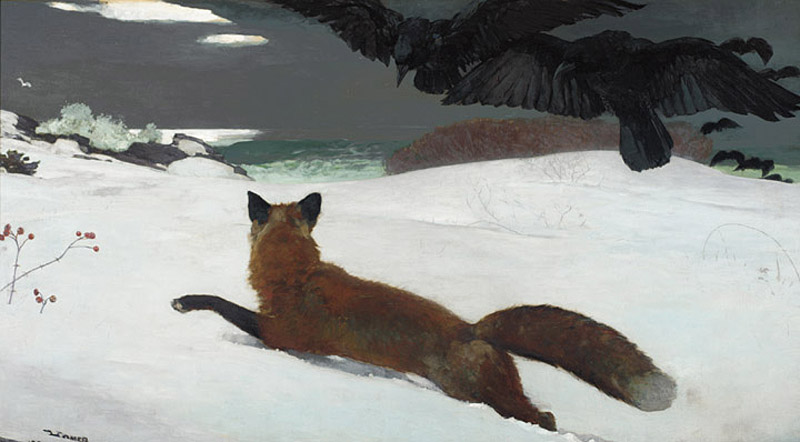

The Gulf Stream, supported by watercolor studies, is the show's marquee paradigm, a narrative drama that represents Homer's last major thought on race: a Black man stoical in the face of death. Here is a crosscurrent, the confluence of themes that fascinated Homer for decades: the fraught experience of Blacks after the Civil War, and the reckoning with mortality. Homer would have been appalled by our desire to look under the hood—"I regret very much that I have painted a motion picture that requires whatsoever description"—though the truth is he left a wealth of provocative clues. Alas, the artist has no take chances to correct interpretations posthumously. A onetime director of the Met saw the hovering crows in the great The Play tricks Hunt as the embodiment of Freud'southward "nightmare of the flying penis." Sometimes, a crow is just a crow.

At the age of twenty-5, Homer covered the Ceremonious State of war every bit an illustrator for Harper's Weekly. The frontline drawings inspired his first oil paintings. Sharpshooter shows a Union soldier perched in a tree, booted foot outlined confronting a white sky; Homer later revisited this odd point of focus in a far improve canvas, The Life Line, in which an equally anonymous man'due south shoe is silhouetted against white water. In one painting the protagonist is charged with taking life, in the other with saving it. Both characteristic Homer'south gift for visual deflection, frustrating our desire to see the men'southward faces and giving united states a good wait at their feet instead. In Defiance: Inviting a Shot before Petersburg, a panoramic and beautifully painted mural is evenly divided between a dark ground plane and a deject-laden heaven. This is no hymn to American wilderness, nor a subtle innuendo to a nation asunder. At the center stands a Confederate soldier driven mad by trench warfare, taunting a Union marksman. Professional snipers like the one Homer depicted in Sharpshooter were accurate from a mile afar, so the result is predetermined. The year was 1864, Homer was 20-eight, and he had found his motif: lethal scenarios tucked into gorgeous landscapes.

With the exception of a caricatured figure in Defiance: Inviting a Shot before Petersburg, Homer'southward depictions of recently emancipated Blacks avoid condescending stereotypes. His straightforward and sympathetic appraisement of Black culture was exceptional for the time. Dressing for the Carnival is his nigh visually rich painting of the Ceremonious War era, the celebratory silk patterns contrasted against a frieze-like positioning of figures. The preparation takes on a sacramental significance, an essay in nobility that is characteristic of Homer'due south figures regardless of race or gender (the exhibition begs for a related show that would concentrate solely on Homer's humanism). Years later, the dazzling watercolors produced during Homer'due south Caribbean trips frequently fixed on the Black men and women who worked the body of water. The environment are dominicus washed and spectacular, but there is danger in the tropic heat. Northern hemisphere or southern, the sea is indifferent. The man who lies upon the deck of a broken boat in The Gulf Stream is a afar cousin to the fishermen in The Fog Warning and Lost on the K Banks. Homer's pessimism, grounded in our ultimate insignificance before the forces of nature, makes him a spiritual heir to another master of marine painting who began equally a graphic illustrator, Turner.

For years, my favorite seat at the Met has been in the American fly, in front of Maine Declension, Northeaster, Moonlight, Wood Island Low-cal and Cannon Rock. In their view of nature every bit inherently dynamic rather than pastoral, these are paintings unlike whatever that preceded them in American fine art. Sometimes comparisons are fabricated with Courbet's seascapes, but nobody had approached the specific sense of the tactile, the full-bodied weight and violence of Homer'due south vision. Really, nobody has since. In removing the figure and any obvious narrative devices, the viewer is invited to behold the tempest and churn without a surrogate, and to practise so at perilously shut range. Each sail is designed differently, the relation of h2o to stone ever fluid and always right, as if at that place were no possible alternative to the certitude of the compositions. Fluid is a deceptive word to describe the seascapes; nigh artists set up on aqueous qualities, on making water look wet. Homer's paintings at Prouts Cervix followed decades of study, peculiarly of the grandeur that could exist elicited from the repetition of surf hitting land. He was more than interested in primal force than mimetic surface. His waves are roughly every bit fluid as wet cement.

In another sense, that of pure motion picture making, surface is vital. Homer commonly devoted extensive time and idea to the big oils—an exception was Woods Island Light (not in the testify), which was supposedly painted in i spontaneous session as Homer stood in the moonlight beneath his studio. After exhibiting Northeaster with two figures standing on the rocks at left, he submerged them in the column of ocean spray we see today. The revision emphasized a contrast in the tactile qualities of dense, variegated cream and polish, immovable rocky mass. Homer found—or invented—cliffs the color of coal, their ebon richness pocked with maroon passages and unclouded by the sea spray that covers everything with a fine mist. At that place is a story that Homer's brother built him a studio on wheels, which he moved about the rocks to work from different vantage points. A biographer dismissed the idea as impracticable, since the view through the windows would have been obscured past spray. In Maine Coast, the sea over again moves beyond the canvas from left to right, this time swallowing much of the shoreline. It seems unlikely that Homer stood this shut to the action, merely rather, contrived the scene in the studio from sketches and memory. Thick white spume, practical with brushes and knives, overwhelms the foreground rock, division information technology into a half dozen separate facets. In a moment the water volition withdraw and the promontory will be revealed in its fullness. This was Homer'southward blueprint playground, an arrangement of black and white masses, pushing against each other until the patterns roughshod into place like the tumbler of a lock. There are no surfaces more complex, or rewarding, in American painting. Generations of painters responded: George Bellows sought the dramatic buoyancy; Frederick Waugh emulated the romantic aspects and Marsden Hartley abstracted the essential power. Mayhap Franz Kline came closest in sheer pictorial impact, and his paintings aren't even about the Maine seascape, equally far as I tin tell. In his ability to structure pigment that evokes the solid stuff of ocean and stone, Homer was unmatched.

In the finish, Homer didn't need to tell a story, but when he did it was a ripper. The two belatedly animal paintings are here, The Fox Hunt from Philadelphia and Right and Left from Washington. Again, there's zilch in our native lexicon that comes shut. The Trick Hunt was his largest sail. Information technology shows the title animal, an admirable burnt orange specimen, trudging through mid-wintertime snow while being pursued by hungry crows. Homer repainted the birds subsequently a critique by the local stationmaster; together, they subsequently spent iii days luring crows with corn so Homer could draw them in flight.

Homer painted Correct and Left while recovering from a stroke. The composition is like to that of an Audubon print, with two goldeneye ducks arranged asymmetrically. Pinioned against the ocean, the ducks mesmerize by virtue of their grace. The birds rise from a moving ridge trough, filling the foreground plane at the moment they're struck by gunshots. Subsequently years of leaving it to our imagination, Homer has brought united states the exact instant of decease. The artist has placed us non merely close to the drama; he—and we—are looking straight down the muzzle of a shotgun. The blast that takes out the ducks hits u.s.a., besides. Left and Right was Homer's final major work. He died the next yr.

The themes that Homer attempted in oils are echoed in his watercolors, though less obviously. The tendency has been to assess them primarily for their freedom of execution and vivid color. It's understandable that Homer'south technical acumen every bit a watercolorist is a distraction; the pattern and broad washes of color in Natural Span, Bermuda render the horizontal figure of a British soldier in the lower correct corner a bit incongruous. Maybe that'southward what Homer was getting at. In The Turtle Pound, one human being hands a turtle to another in a holding tank. The curators may be stretching things by noting that turtle meat had become a effeminateness in the U. S. and U.k., thus making the painting an implicit comment on colonialism. Is the appearance of a British naval flag in Hurricane, Bahamas, a tacit reference to political turmoil? I'm skeptical of the conclusion to run into veiled commentary in everything Homer painted, yet the show's larger signal, that the artist was fascinated past disharmonize throughout his career, is valid. That Homer'due south narratives could be cryptic or presented surreptitiously merely deepens the paintings' effectiveness. On first viewing, one is unlikely to recognize that the deer in the glowing watercolor An Oct Day is swimming to escape a hunter in a distant canoe; the animal'southward dreary fate is told in an oil, Hound and Hunter. Burnt Mountain is intriguing as a technical do—the layering of mountainside, figures and sky is complex—but a landscape painter doesn't cascade that much energy and insight into a turbulent swath of clouds unless something is up. The roots of an upturned tree that one time took nourishment from soil now appear to radiate from the head of one of the resting hunters. The consequence is inexplicably eerie.

Such is the depth of the testify that there are major works I haven't mentioned. Snap the Whip, Breezing Upwardly, 8 Bells,Undertow and After the Hurricane, Bahamas, are landmarks in Homer's career and essential images in a survey on American painting. I'chiliad certain someone has compared him already to Twain or Hemingway, every bit possessing a uniquely American colloquial. Homer can be seen every bit a realist and a mythmaker, as pure painter and storyteller. His motives and meanings are open to interpretation, nevertheless they remain, as he would have wished, stubbornly cryptic.

Winslow Homer: Crosscurrentsis on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art through July 31, 2022.

Source: https://asllinea.org/winslow-homer-crosscurrents/

0 Response to "Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art New York George a Hearn 1906"

Post a Comment